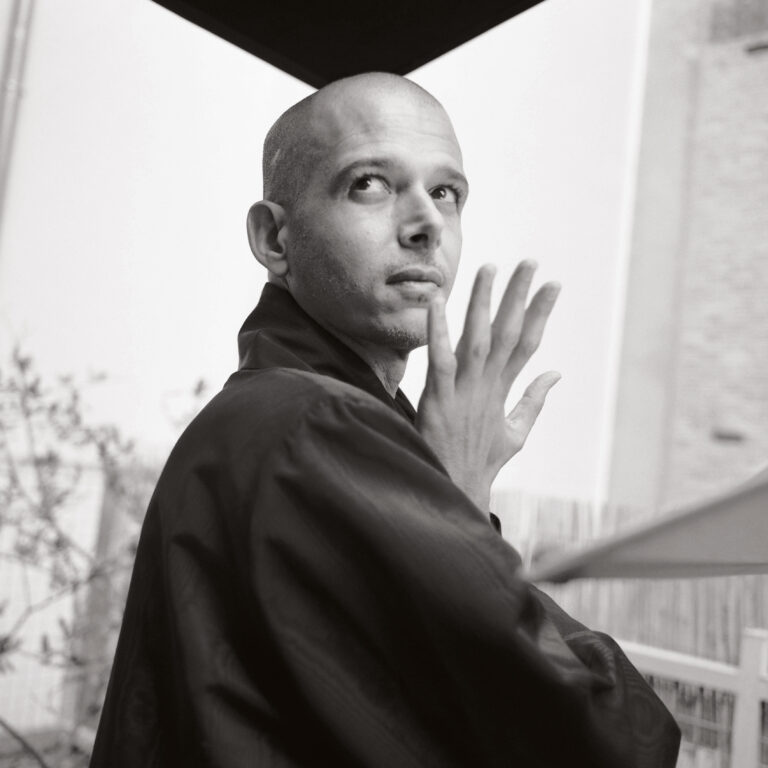

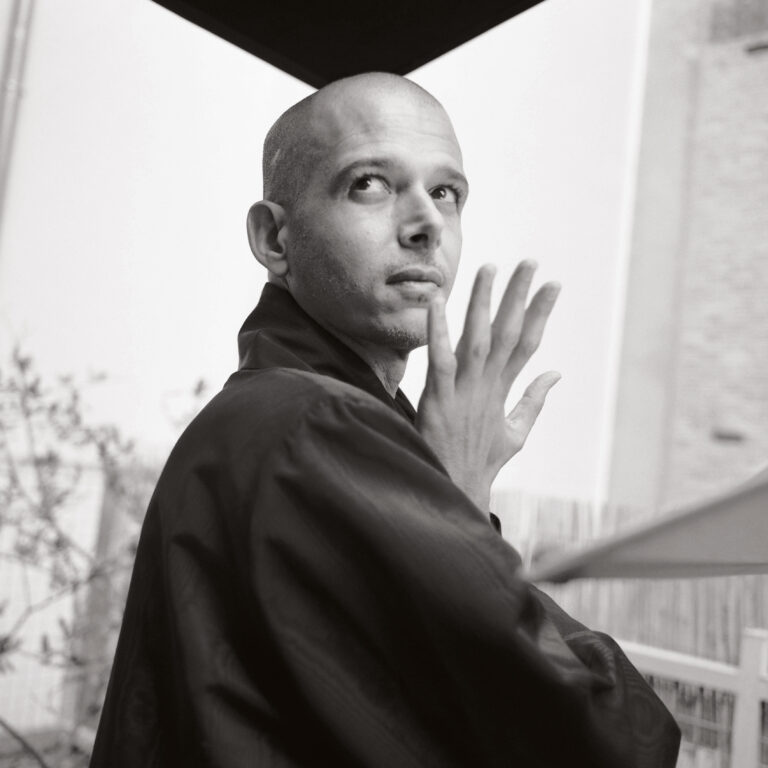

Abdellah Taïa

A writer dresses up

How to be completely outspoken and free from shame. As a kid the lauded Moroccan author Abdellah Taïa forced himself to learn French, the language of a country that colonized his, simply because he knew he needed to escape. Now, Paris-based Abdellah treats the world to highly autobiographical books, films and plays, which often deal with the difficulties of growing up gay in Morocco. He isn’t in it for the shock, but to spread love and excitement, whether he’s writing, thinking, talking or dressing up in some grand and contrasty looks.

From Fantastic Man n° 34 – 2021

Photography by MARK PECKMEZIAN

Styling by JULIAN GANIO

A writer, writing: correspondence with Abdellah Taïa

Dear Abdellah, we know you are a writer and a film-maker. Are we forgetting any other job? What other titles apply to you?

I’m currently doing a play in Paris, at the Théâtre Ouvert. It’s called ‘Comme la mer, mon amour’ (Like the sea, my love). I co-wrote it with the actress Boutaïna El Fekkak. We are both directing it, and we both act in it. It’s the story of two Moroccan immigrants in Paris. She comes from rich Morocco. He is gay and from poor Morocco. They are best friends when they arrive in Paris in 1997. They help each other in order to survive in this new world. One day, the girl abandons the guy. Many years later, they meet on the street by chance. The guy wants to know why she left him without any explanation. She says that she doesn’t remember. And then he starts to talk to her about the old Egyptian movies they used to watch together. It’s a play about the end of friendship and about how melodramas influence our lives. So this all means that I am now in theatre as well, as a writer, an actor and a director. Boutaïna and I are already working on our second project.

Are you an activist first and a writer second?

I am a writer and a film-maker first. I came out as gay in 2006 in Morocco. Since then, I haven’t stopped writing articles about LGBTQ+ issues in Morocco, in France and around the world. So, yes, over the years, I’ve become a kind of activist. I use my legitimacy as a writer to defend people. Four years ago I did a creative writing class with gay and transgender sex workers, run by the Parisian association Altaïr. These sex workers were mostly immigrants and had many problems in French society. I was supposed to do the class for a month or two but it lasted a year and a half. I’ve never felt more useful than there, in that place, with these absolutely great and inspiring people. To be a writer, or a filmmaker, is to be with others. Other bodies. Other voices. Other stories. To listen. To listen without prejudice (which is also the title of a magnificent George Michael album).

Do you have a book, film or other project in the works or about to come out?

When, and what is it? Right now, I am focusing on my play. We are going to tour it in France, Belgium, Morocco and other countries.

How many books have you written?

Ten books, I think. Maybe more. I am a very superstitious person, so I don’t count.

How did you go from speaking Arabic to writing in French?

I was born in Rabat in 1973 into a very poor family. I’m the eighth of nine children. Like many Moroccans, we spoke Arabic. French is spoken in Morocco only by the rich. I hated French. It was a language that separated the elite from the rest and accentuated their power and domination. But, in order to survive in the Moroccan society, to find a job, I had to learn French. What a shame! Even today, we are still dominated by colonialism. I remember clearly how I felt when I first arrived at university in Rabat: my French was very, very bad. In order to improve, I started a diary in French. I wrote in it everything I wanted, with no intention of being a writer. The only intention was to be as good at French as the rich Moroccans. But a miracle happened, in the many cheap notebooks I used as diaries: not only did I master French quickly, not only did I become the best student in my class, but I discovered in me the ability to write. The ability to transform my obsessions into written stories. That was the turning point of my life. In these notebooks, I also spoke to myself as a gay person. I spoke to Abdellah, who was so alone, raped by so many people, insulted, humiliated. Abdellah, who was so angry. Crying Abdellah. I freed that Abdellah. I invented another Abdellah. Now I write novels, screenplays, plays, articles, all in French, but it’s a French that’s heavily influenced by Arabic. A language is always more interesting when it’s not used in a pure way.

Do you have a favourite word and why?

My favourite word is M’Barka. It’s the name of my mother (1930–2010). In Arabic it means “the one who is blessed” or “the one who brings the blessing with her to other people.” My mother was born into a world that didn’t help her to understand her gay son. But she didn’t reject me. She was not particularly fond of me, but she didn’t stop me from studying. She used to save six dirhams a day so that I could take the bus from the city of Salé to Rabat. She pushed me as much as she could. She’s no longer here now, and I forgive her for not protecting me. Every day I say her name. M’Barka, M’Barka, M’Barka. I recognise her fight as a woman, as a mother. I see what she did for us: feeding a family of ten every day, for 45 years.

How many languages have your books been translated into and in what language would you still like them to be translated?

I am very, very lucky. My books have found readers around the world. I have been translated into many languages. My novel ‘A Country for Dying’ was even translated into Kurdish in 2016. I was so, so, so happy with that – my words and my literature, full of LGBTQ+ characters, in Kurdish Iraq. It’s a true miracle. One day, I would like to be translated into Japanese. I am obsessed with Mizoguchi movies. He is my link to Japan. He is a master, my master.

What’s the ideal retail price for a book?

Books should be free for everyone. When I was a teenager, I used to steal books sometimes. I had no money to buy them. Unfortunately, there’s still this idea that books are made only for the bourgeois and the elite. I want people like me, in the poor neighbourhood I grew up in, to feel that books are made for them, too.

It’s beautiful to be naked, you said in an old interview. How does that relate to the fact that you also happen to look great in the latest fashion?

I grew up with ten people around me in a three-room house. It was very crowded, and I loved it. I love to be like a cat lying on other cats, day and night, day and night. My idea of life, of the world, is that I am not alone. There are other bodies with me, next to me, against me, even when they are not with me. Even when we’re alone, we are not completely alone: we have memories, ghosts, vibes, reincarnated things around us. I believe in all of it. The invisible world. Death is not the end, death is not death. And, of course, as a good Moroccan, I believe in possession, in ritual, in sorcery, in magic. The fashion shoot was so wonderful, so happy. We were playing, joyful, all day long. We talked all day long about our obsession for the divine Sade. Everything was easy and light and happy, happy, happy. I played with the clothes. No shame. No fake timidity. One day, though, you have to do a shoot with me naked. Let me know your thoughts.

Photographic assistance by Victor Gueret, Maxime Sicard and Emma Corbineau. Styling assistance by Mayu Kawasaki. Grooming by Caroline Fenouil at Bryant Artists. Casting by Ben Grimes and Tiago Martins. Production by Cinq Etoiles Productions.